What it’s like to narrate your own audiobook

16 hours concentrating in a warm, windowless box - and there's a huge flaw

Many believe poetry is written to be spoken aloud, not read on the page. To a certain extent, the same applies with audiobooks.

Whilst I’d never compare my book Operation Pimento to poetry, the flaw remains- I didn’t write it to be spoken aloud.

It is the same way some literature teachers complain of making schoolchildren read Shakespeare plays instead of watching them. Similarly, read any Churchill speech and I guarantee the words will have less punch than listening to the great man breathe life into them with his magnificent oratory.

The chorus of the Beatles’ best-selling song, She Loves You, reads:

She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah

She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah

She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

If I had read these words these words on a page in the cold light of day in 1962, I would have told Lennon and McCartney to go and work on something better.

My point is that writing changes vastly for whichever medium you are intending people to consume it.

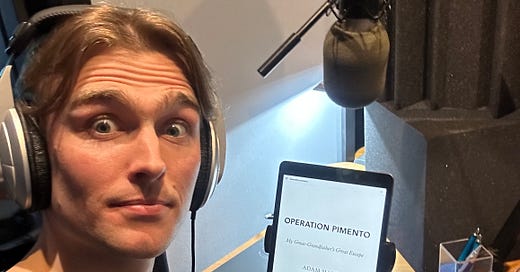

For anyone who has ever written speeches, plays, songs or poems, this is obvious. But for me, this was rammed home when I narrated by book last week, something I’m told is fairly standard practise for books with a personal element- even if the author has no idea what they’re doing in front of a microphone.

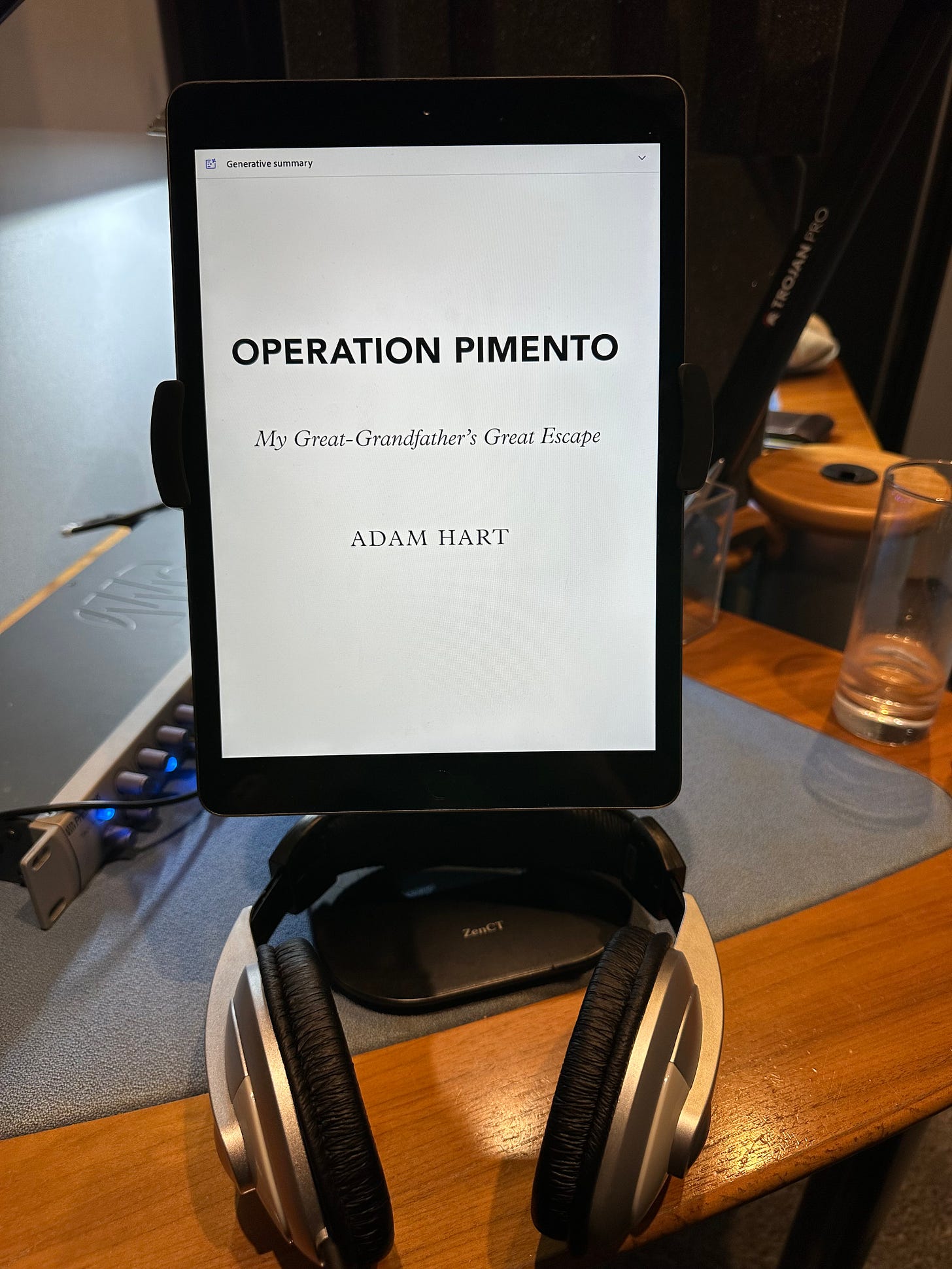

It all happens in a tiny soundproof box where you read by scrolling on an iPad fixed to a stand in front of you (turning the pages of a physical copy would make too much noise). The box is very warm, windowless and totally cut off from the outside world, aside from a small window that looks into a dark recording studio office where the poor producer who has to listen to the whole thing sits.

Within the first few paragraphs, I realised there is something brutal about reading prose you have written aloud. If a sentence lacks authenticity or punch, it’s magnified when spoken in a way that just doesn’t happen with reading. Wandering clauses, questionable comma placement, woolly metaphors, all have nowhere to hide in front of the microphone.

Sentences that look respectable on a page fall apart under the scrutiny of being verbalised. No one likes the sound of their own voice, and I stumbled through the first few pages awkwardly, gripping my hands tightly together and sweating.

The first chapter also taught me I couldn’t narrate in line with the grammar I had written, i.e. pausing for breath at commas and full stops. I never quite realised how much I enjoy a long sentence, but within ten minutes of narrating I found my lungs bursting as I tried to match my written word. Inserting breaks into sentences to breathe comes slowly at first, but by the end, with the formula imprinted into my head, I could punctuate sentences on the iPad screen before getting to them.

It is still an exhausting process. You’d think sitting in front of an iPad all day reading and speaking would not be tiring. But the act of reading words, translating them into speech in your head, then delivering them without the tiniest slip of the tongue or mispronunciation, whilst accounting for pitch differences in dialogue, takes a huge amount of focus. I couldn’t manage more than an hour in any one go.

It's also a physical drain. Your eyes ache from staring at the iPad. Your throat aches from speaking clearly and annunciating every syllable. Your body aches from sitting perfectly still. The slightest brush of your foot on the carpet would be caught by the mic and mean restarting the sentence. The same goes for the smallest of tummy rumbles, voice breaks and that weird gurgle your throat occasionally makes. Even with a pillow, I found sitting completely still uncomfortable after a while, but shift your weight just an inch and you can be sure the producer’s voice will sound over the headphones saying ‘start again please’.

After the first day's recording (roughly seven hours long), I left feeling as though I’d done a seven-hour drive on roads I didn’t know. Descending to the tube, I automatically read the station signs in my head like I had been reading the book, before missing my stop. Later, in the minutes of semi-consciousness before sleep, I felt snatched clauses of sentences whirring around my brain.

It can become maddening when you get stuck on a particularly tricky sentence with multiple clauses. Restarting the sentence for the third or fourth time, you sense the tricky part arriving- you know exactly what to do- here it comes- only to fluff it again. Somehow you just have to not overthink it, take a breath, speak slowly and pray the words come out alright.

There were also more practical, mundane difficulties too. With 70 per cent of my book taking place in France, Switzerland and Spain, pronouncing names and places threw up difficulties for my distinctly unilingual vocabulary. By some miracle, the producer spoke French and Spanish fluently, and his German was good too, so he sped up the process greatly by telling me how to pronounce words. (Catalan remained a challenge, however).

What he couldn't speed up were words or phrases that are just difficult to say correctly in English. For me, these included ‘Polish soldiers’ (try saying it), ‘Jewish schoolchildren’ and the word ‘linoleum’. I also realised I have not been pronouncing the words ‘alias’, ‘mischievous’ and ‘secretary’ correctly my entire life.

Dialogue was also challenging, though I didn’t attempt French, Spanish, American or German accents for fear of turning it into some sort of Allo Allo out-take. It just feels cringey reading conversations aloud and it made me realise how hard it is to write realistic dialogue. The swearwords made the awkward Brit within me wince too.

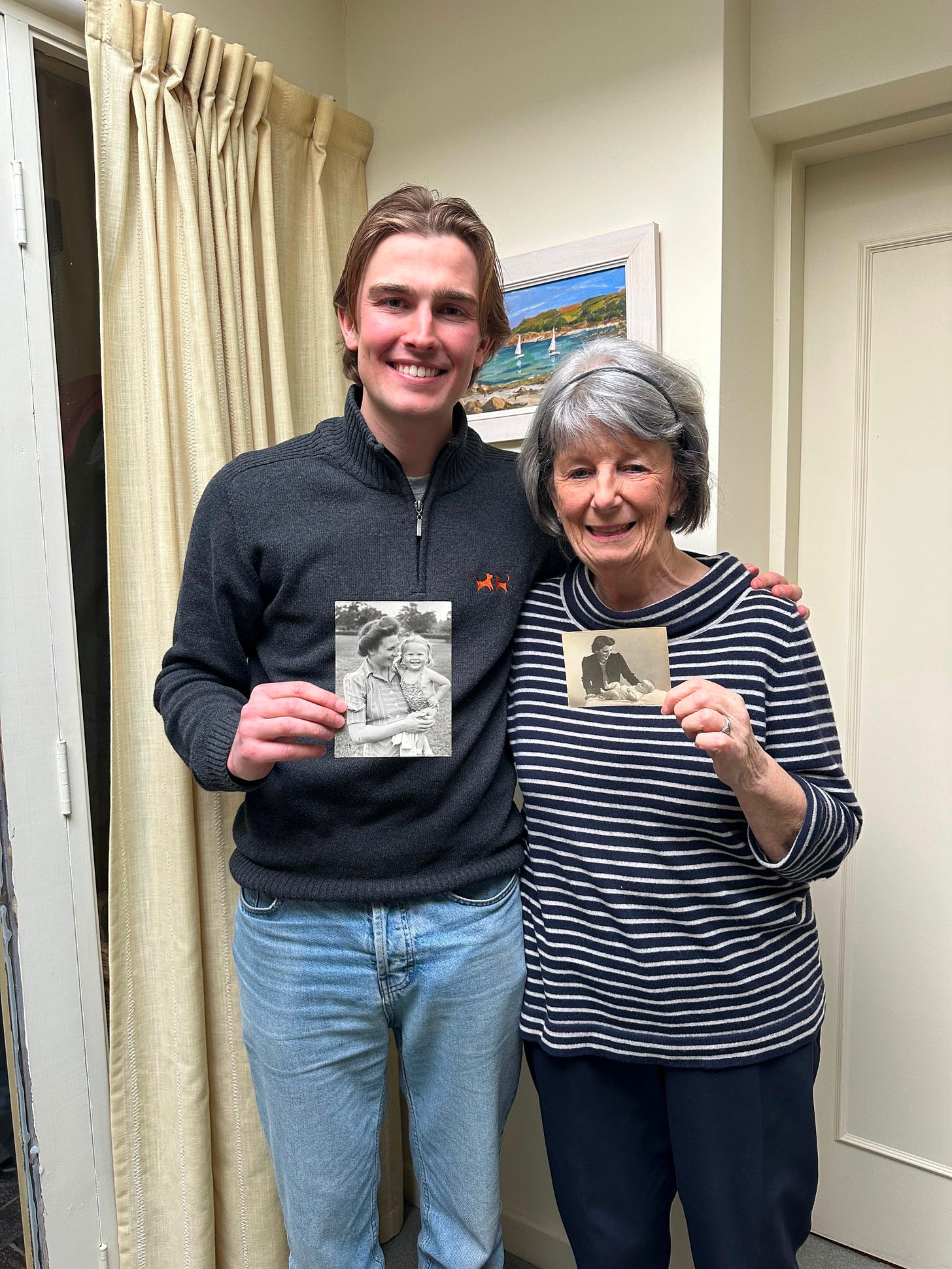

Without wanting to blow my own trumpet, another uncommon yet sometimes potent obstacle was not getting choked up as I read passages from my journey retracing Frank’s escape in 2022.

Sitting in the warm little box cut off from the world, I was transported back to lunch in the garden of a Pyrenean farmhouse where, with the granddaughter of the guide who’d led Frank over the mountains at grave personal risk, we toasted our ancestors.

I was taken back to walking into Gibraltar at dawn after sleeping in a hedge, dawdling over the international runway with the sun rising from the Atlantic as Spanish commuters streamed past me.

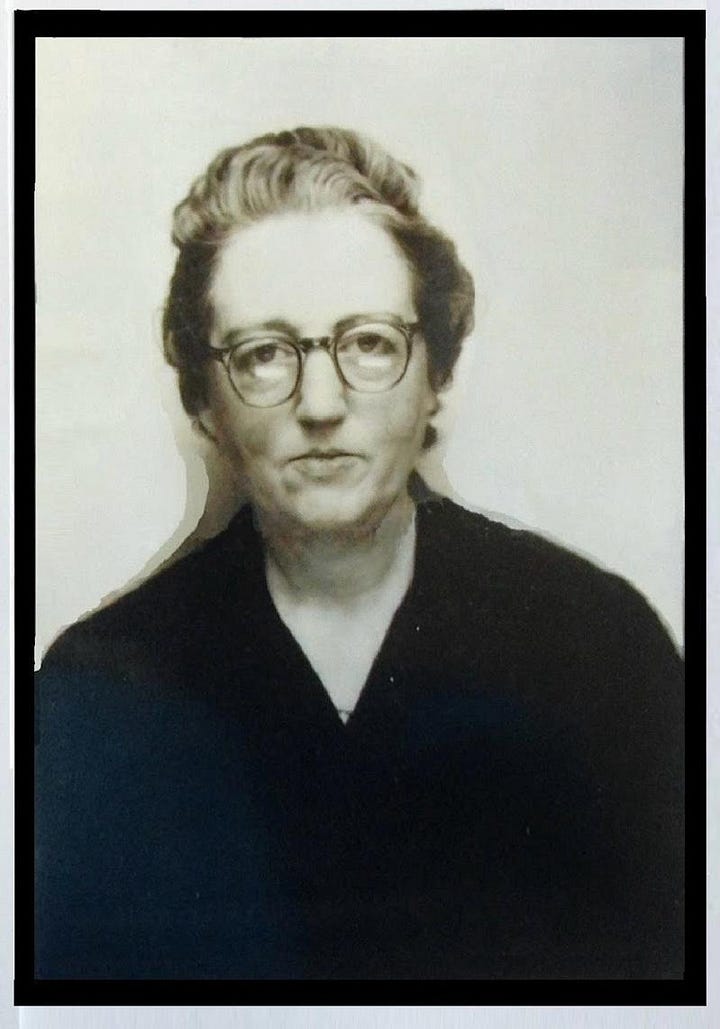

Most poignantly, I was taken back to meeting a wonderful woman called Helen, the daughter of Frank’s navigator who was killed the night they crashed in France in 1943. Helen had never met her father as she was born after his death.

She gave me the letters Frank had written to her grandmother in which he confirmed her son was dead and his last words. They’re included in full in Operation Pimento and I defy anyone to read them without their voice cracking momentarily.

After 16 hours recording over two days, I read the last sentence and left the box. The producer and I were happy with the job, and like many audiobook newbies before me I felt I had really gotten the hang of it toward the end. I needn’t worry, the producer assured me, as most people listen to audiobooks on 1.5 speed apparently.

I asked about the editing process, namely the removal of the thousand or so mistakes I made during the recording, and was surprised to learn it would only take a day or two, though at 70,000 words (about 10/12 hours) my book is quite short.

The producer told me how in the beginning, audiobooks were limited to three hours on a thing called a cassette, or six hours if you had a thing called a double sided cassette. Initially, they were only bought by airlines wanting to offer passengers something to listen to if they didn’t want to watch the film being projected at the front of the aircraft, something I could not believe as a Gen Zedder. Now audiobooks are a £1billion industry in Britain, a stat being driven in part by young men, historically the least likely section of society to buy and read a book but who have discovered them through Spotify.

Emerging from the studio into the harsh daylight and sodden streets of London, I’m told a monumental thunderstorm had just blown through, not a bit of which I heard in the box.